Is Dolls Kill Fast Fashion in 2026? Our Verdict

December 26, 2023

Is Guess Fast Fashion in 2026? An Honest Look

February 1, 2024Windsor Fashions targets young women seeking chic yet affordable apparel for any occasion. However, many shoppers still wonder: is Windsor fast fashion? A closer look at pricing, trend cycles, fabric choices, and supply-chain transparency reveals patterns typical of fast fashion — even when the price tags look slightly higher. In this guide, we’ll break down the aspects of Windsor as a brand, diving into its ethics and sustainability. Without further ado, let’s dive in.

Is Windsor Fast Fashion?

Despite slightly higher prices, Windsor exhibits core fast fashion characteristics – trend-driven, low quality, unethically produced clothing. By targeting young consumers with microtrends and failing to provide transparent audits, Windsor promotes overconsumption through the same environmentally and socially exploitative practices as other fast fashion retailers.

Windsor’s Higher Prices Don’t Equal Ethical Fashion

Fast fashion thrives on the illusion of ethical quality through inflated prices. According to Statista, the average price of a dress at leading fast fashion brands ranges from $15 to $40. For example, a typical dress costs around $16 at Shein and under $50 at Zara. Despite the slight price difference, both qualify as unethical fast fashion.

Windsor’s top pricing falls around $40 for dresses and $35 for shoes, which means it’s upselling its products for almost twice the average price. While exceeding extremely low-cost retailers, this remains well within fast fashion parameters, especially when compared to Zara and H&M.

| Brand | Dress Price (avg) | Shoe Price (avg) | Price Positioning | Overall Tier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Windsor | Up to $40 | Up to $35 | Moderately priced within fast fashion | Mid-tier fast fashion |

| Shein | ~$16 | Under $25 | Extremely low-cost | Ultra-budget fast fashion |

| Forever 21 | Under $30 | Under $30 | Very low-cost | Budget fast fashion |

| H&M | $20–$50 | $25–$40 | Comparable to Windsor | Mainstream fast fashion |

| Zara | Under $50 | $40–$70 | Slightly higher than Windsor | Upper mainstream fast fashion |

So, why is that so? Moderately higher price points perpetuate an illusion of ethical sourcing and high quality. In reality, however, they mask exploitation, as brands charge more while relying on the same unethical systems.

Is Windsor Expensive But Still Fast Fashion?

As evidenced by Urban Outfitters, inflated costs signify nothing regarding sustainability or labor practices. So, do not confuse higher prices with a ‘green premium.’ In general, higher price points in fast fashion serve a purpose – they make consumers believe that a brand isn’t fast fashion.

Urban Outfitters’s price range deceives the consumer into thinking that they’re purchasing better or higher quality clothes, when in reality they are buying something equally poor, if not worse. The reason why this works is that most consumers deem mid-range brands, such as Cider, YesStyle, and Aritzia, of higher quality, as compared to dirt-cheap fast fashion labels, such as AliExpress and Shein, without looking into their supply chains and assessing objectively whether they’re fast fashion.

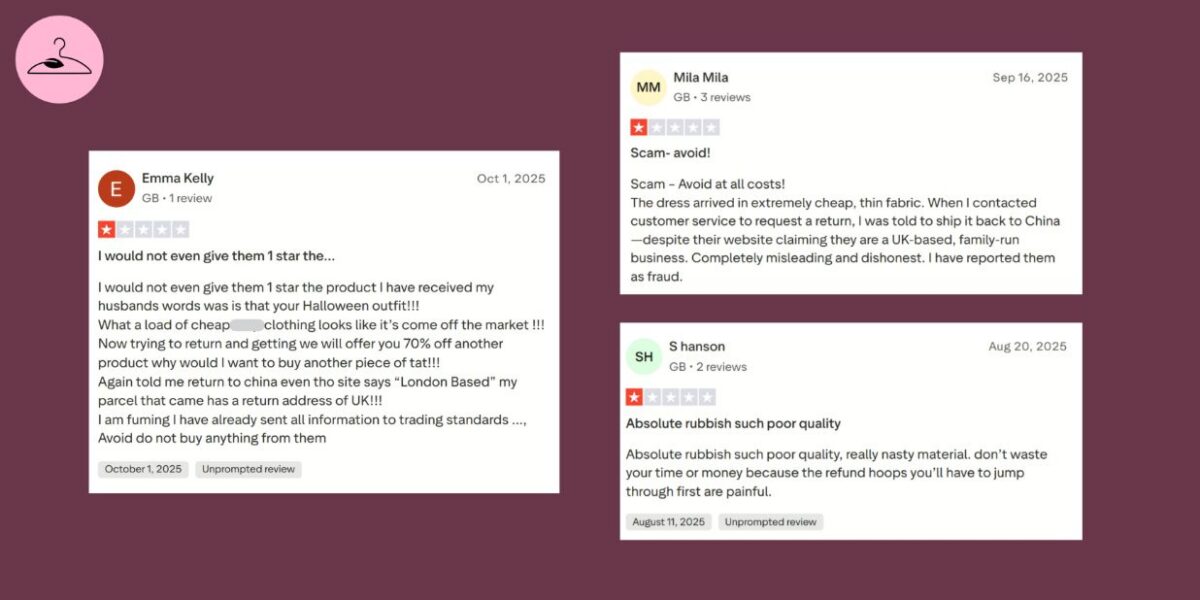

Windsor’s Reviews: Quality & Return Issues

When it comes to the quality of Windsor’s products, a Reddit user describes it as an upgrade from Forever 21 – “not top quality, but good for the prices.” Another user deems the quality poor, ranging from “okay-terrible”, hence it’s reasonable to assume that the brand carries conventional fast fashion products that are often hit-or-miss

After all, without fundamental change, elevated expense is meaningless, serving no purpose other than making consumers pay for the label or the in-store experience.

Pro Tip: when shopping, always scrutinize fabrics, rather than being fooled by prices – this way, you’ll be able to concentrate on genuine quality, rather than the brand experience or false indicators of quality.

Windsor: Targeting the Fast Fashion Audience

The brand’s ethical stance becomes clearer when scrutinizing the ‘Trending’ section on its website. Targeting the fast fashion audience (women between 18-24 years of age), the brand puts an emphasis on microtrends, categorizing its apparel into sections, such as ‘Baddie Outfits’, ‘Y2K Outfits’, and even ‘Normcore Fashion.’

By this, Windsor taps into the power of TikTok trend cycles in order to connect with the Gen Z consumer – the primary target consumer of fast fashion. The brand promotes overconsumption, urging young consumers to base their identities around fleeting microtrends.

However, this is not the whole picture. More than 30% of Windsor’s visitors are aged 25-34, so how does the brand tailor its advertising to this key demographic? Producing in-demand occasion wear designs, the brand replicates the current fashion zeitgeist, leveraging AI-driven search advertising and user-generated content from social media.

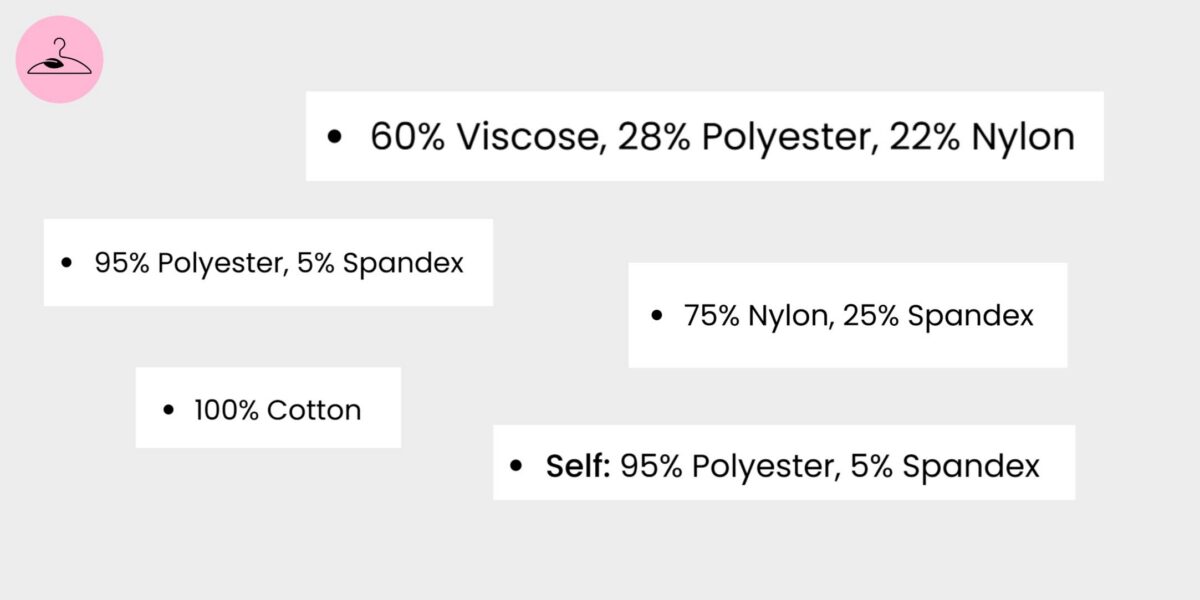

Windsor Mostly Uses Synthetic Textiles

Exploring the fabric composition of most apparel at Windsor, the dominance of synthetic textiles becomes crystal clear. Most of the brand’s products are made of the following problematic fabrics:

- Polyester – derived from petroleum and treated with harmful chemicals, such as antimony and ethylene glycol, polyester can decrease fertility in both men and women.

- PU – the so-called ‘vegan leather’, PU is basically plastic that doesn’t biodegrade.

- Polyamide – a synthetic material that releases microplastics during washing, which triggers neurotoxicity and adverse immune responses in fish

- Acrylic – the residual monomers of acrylic have been labeled as carcinogenic by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

These toxic synthetic materials can be detrimental to consumer health, as well as the environment, due to the presence of azo dyes, heavy metals, formaldehyde, and other harmful chemicals. Considering that synthetic materials break down for hundreds of years, this is quite alarming, as they release toxic chemicals into the atmosphere, marine life, and nearby communities during the process.

So, before shopping at brands like Windsor, it’s crucial that you question their use of toxic materials. To make a difference for a better industry, we all should reject fabrics that slowly poison us and instead, choose natural, non-toxic materials.

If you haven’t identified slavery in your supply chain, it is likely that you are not looking in the right places

Tara Hounslea for Drapers (2017)

Stances Against Modern Slavery: A Facade for Compliance?

While Windsor claims to oppose modern slavery, their statements require further interrogation. Sadly, the language used by the company obfuscates more than it illuminates. The brand asserts that suppliers must sign agreements prohibiting slavery and labor exploitation. However, documents alone cannot substantiate ethical practices within supply chains, raising questions on the ethicality of the brand.

The company says it performs audits annually, yet provides no transparent details on the rigor or independence of such audits. Ambiguous phrasing like “may include unannounced audits” reveals potential loopholes, rather than steadfast accountability.

The Cost of Weak Reporting and Empty Reform

Through poor reporting, Windsor reflects an alarming statistic from Oxfam, according to which fashion brands only pledge to fight modern slavery, however, fail to tackle the issue in reality. In fact, 33% of brands struggle to meet minimum reporting requirements, demonstrating a systemic failure across the industry to eradicate unethical labor practices.

Additionally, Windsor states they educate employees on mitigating supply chain risks related to slavery. While important, this education may not catalyze meaningful change without structural reforms. Most importantly, the brand omits transparent data on wages, working conditions, and the remediating labor violations. Such lack of public reporting enables ongoing abuses in the supply chain, which is impossible for ordinary consumers to track.

In summary, Windsor’s flashy promises require further scrutiny. Without transparent, regular, and independent audits, the company remains complicit in structures, which perpetuate modern slavery in the fashion industry.

A Brief History of Windsor

For over 80 years, Windsor Fashions has actively empowered generations of women with accessible, affordable apparel. The Zekaria brothers founded their humble hosiery and lingerie shop in 1937, setting in motion decades of “inspiring fashion” (with questionable ethics).

In 1957, Windsor actively expanded into special occasion dressing, allowing their elegant styles to grace women for life’s most memorable milestones. The brand’s iconic dresses have shaped key moments in the history of fashion, from Jacqueline Kennedy’s era to today’s red carpet.

The brand brought their aspirational styles online in 1998, introducing their inspiring oasis nationwide. By 2015, it had opened 100 stores across the nation. Today, Windsor operates over 200 locations, upholding their founder’s vision – “beauty for all.”

Is Windsor Fast Fashion? The Final Verdict

Throughout the changing tides of fashion, Windsor positions itself as a brand that empowers women through beauty, inspiration, and elegant style. Yet beneath this polished image lies a business model firmly embedded in fast fashion, driven by rapid trend turnover, mass production, and the continued use of non-biodegradable synthetic fabrics that contribute to long-term environmental harm.

Compounding this is the brand’s insufficient transparency around labor practices, vague audit disclosures, and lack of publicly verified data on wages and working conditions — all of which weaken its ethical credibility.

Frequently Asked Questions

Windsor provides minimal insight into its supply chain. While it references a three-tier audit system under the California Transparency Act, it discloses no factory locations, wage data, or independent reports. Transparency remains vague and unenforced, with Good On You rating its labor practices “Very Poor” and insufficiently documented.

Windsor operates as a vertically integrated fast fashion retailer focusing on special occasion wear for young women. Its model relies on rapid trend replication, frequent product launches, and affordability, introducing over 250 new styles weekly. Sales are driven through physical stores and e-commerce, supported by aggressive promotions and trend-based marketing.

Customer reviews frequently describe Windsor dresses as poorly made, with complaints about thin fabrics, weak stitching, inaccurate product photos, and inconsistent sizing. Many buyers report garments tearing after minimal wear and poor overall durability. While a few praise selective items, most feedback highlights unreliable quality and disappointing construction.

Windsor does not promote or highlight any verified sustainable material collections. Most products are made from synthetic fabrics like polyester, viscose, and PU leather, which carry significant environmental impact. The brand provides no certification, recycled content claims, or evidence of ethical sourcing, earning poor sustainability ratings.

Like Zara and H&M, Windsor operates on a fast fashion model driven by rapid production and trend cycles. However, Windsor focuses narrowly on occasion wear and receives more criticism for poor material quality. Unlike competitors, Windsor lacks visible sustainability initiatives or structured environmental responsibility frameworks.

Windsor has no publicly available sustainability roadmap, certifications, or measurable environmental targets. The brand does not disclose plans for reducing emissions, improving material sourcing, or adopting circular practices. Unlike competitors, its compliance remains limited to legal obligations, with no visible commitment to long-term sustainability strategies.